Michigan caregivers are providing care for their loved ones. Who’s caring for them?

Jan 18, 2023

Caregiving: It’s a responsibility that those of us with aging loved ones may inevitably face. And for three Michigan caregivers, the life changes and challenges that come with it have become part of their everyday life.

On some days, it can feel as if those responsibilities might push them to the breaking point.

In collaboration with the Detroit News, One Detroit Senior Producer Bill Kubota and reporters Sarah Rahal and Hayley Harding spent time with three metro Detroit caregivers Nakia Gaither, Doria Rainey and Rosa Eileen Hunter, who are looking after aging mothers, to learn more about the life adjustments that come with being primary caregivers and give a realistic look at the challenges—emotional, physical, and financial—many caregivers face.

Rahal and Harding also spoke with leading experts in caregiving locally and nationally — Bea Rector with the Washington State Aging and Long-Term Support Administration, Dana Lasenby with Oakland Community Health Network and Rita Choula with AARP’s Public Policy Institute — about ways caregivers can receive support in terms of identifying resources,

Plus, One Detroit explores potential solutions other states have adopted that could provide a pathway to easing the financial burdens or discrimination against caregivers.

This collaboration follows up on The Detroit News story published in fall 2022, which was based on a survey, conducted by the New York & Michigan Solutions Journalism Collaborative, showing that often caregivers who need help the most receive the least in terms of support and resources.

Full Transcript:

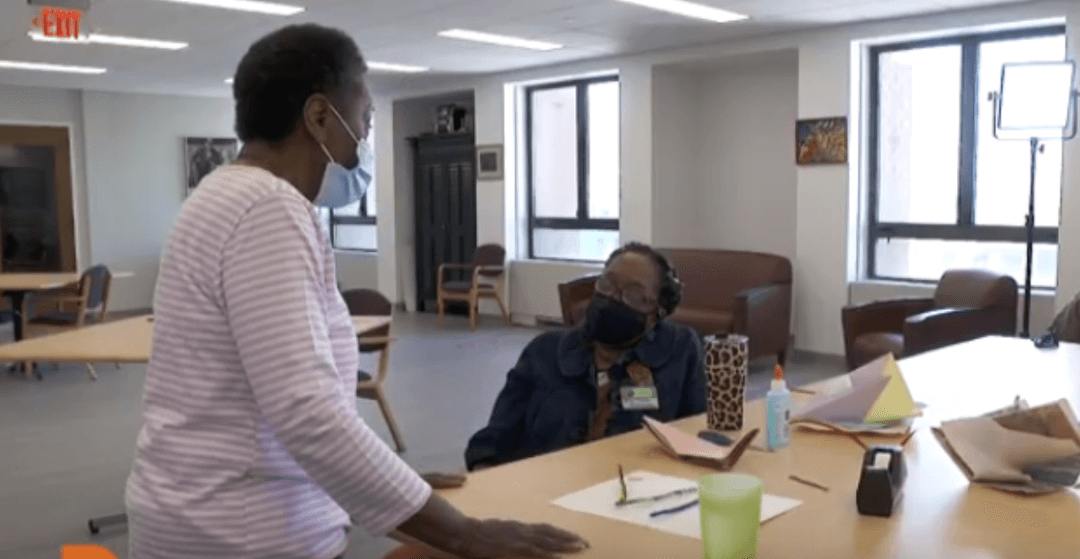

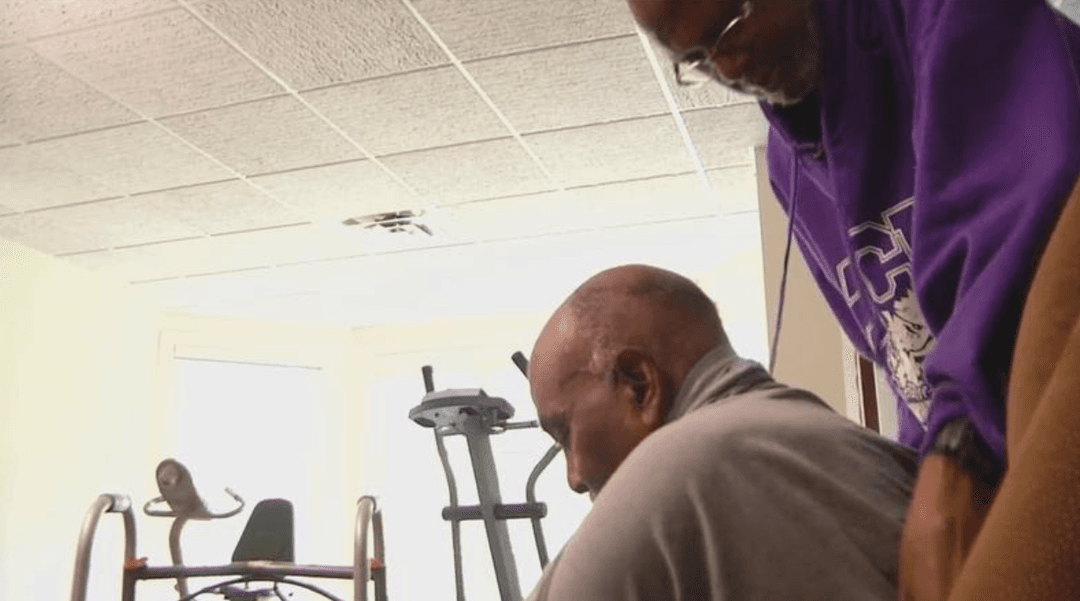

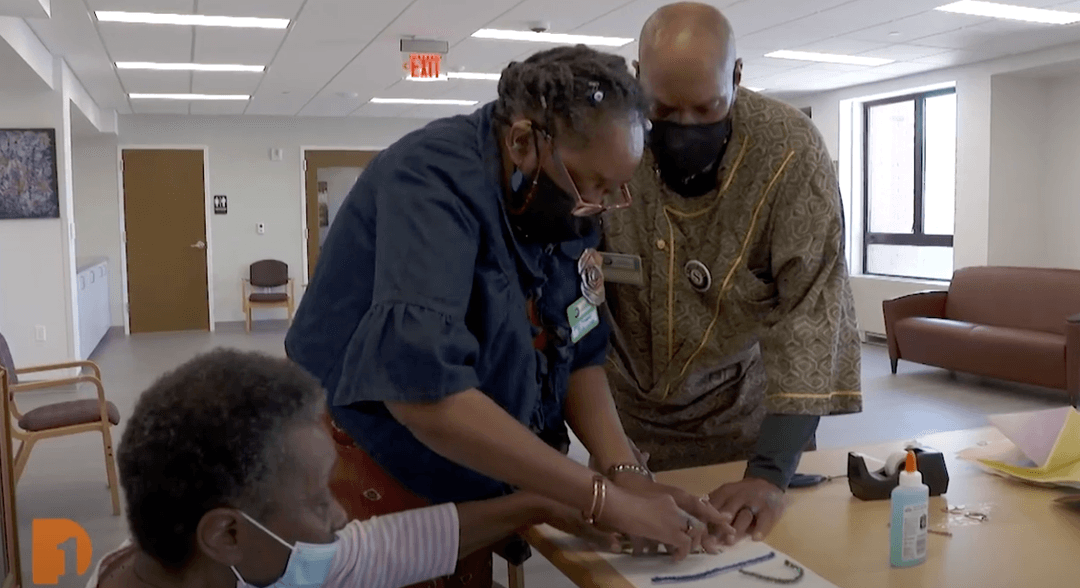

Bill Kubota, One Detroit: Caregiver Nakia Gaither helps her mother, Dorothy Gaither, age 72, get ready for exercise at the YMCA downriver in Southgate.

Dorothy Gaither, Caregiver’s Mother: I thought I’d be physically fit until I was 90. I didn’t think, you know, I’d have to have a caregiver. Well, I didn’t until I caught COVID.

Bill Kubota: Dorothy, retired Nurse, Detroit Medical Center.

Nakia Gaither, Daughter & Caregiver: I get up Monday through Friday between 4 and 4:30.

Bill Kubota: The regimen trips to doctor’s dialysis, physical therapy. The housework and the fight to get healthy again.

Dorothy Gaither: When I got COVID, I got sick. I ended up on dialysis. I almost died on COVID. I was in a coma and everything, stuff I don’t remember.

Nakia Gaither: The thing is, before COVID, my job was I was just her helper. Like I would clean the house, you know. Before she got really sick she was independent.

Bill Kubota: Nakia, age 48, life interrupted. Leaving a career as a performer and personal trainer, traveling the world. Now with Dorothy at her senior fitness class, Nakia leads a spin class down the hall.

Nakia Gaither: Not over yet.

Bill Kubota: A respite from caregiving.

Dana Lasenby, Executive Director, Oakland Community Health Network: The role of a caregiver can be very small to massive.

Bill Kubota: Dana Lasenby is with the Oakland Community Health Network. Connecting caregivers to Resources.

Dana Lasenby: Other family members may be on the peripheral, but that one care member that’s a family member that’s there 24/7 is critical. To the health and safety of that individual, they’re helping to support in their home or spending the night with so that they can work and be a caregiver.

Hayley Harding, Reporter, Detroit News: What does the typical caregiver look like?

Rita Choula, Director of Caregiving, AARP Public Policy Institute: We know that family caregivers are typically caring for a family member, a neighbor, a friend.

Bill Kubota: Rita Choula is with the AARP Public Policy Institute.

Rita Choula: We know that 60% of family caregivers work at the same time that they are really doing a part-time job in providing care for someone else. And many of these family caregivers are sandwiched in meaning that they’re taking care of young children while they’re taking care of older adults as well.

Bill Kubota: In Canton Township, 58-year-old Doria Rainey looks after her daughter’s twin boys. That’s just one day a week. She and her husband work at home. Their company manages websites.

Doria Rainey, Daughter & Caregiver: Yeah, we’re a team. Yeah, we are a team. So I’m thankful that my daughter is here because if she wasn’t, you know, it would be kind of hard.

Bill Kubota: The big lift? It’s her mom with a recent onset of dementia.

Doria Rainey: Basically have three lives going on for me, taking care of myself, my mom, and then the business. Caregivers know what caregivers go through. And other people they, you know, they don’t hear it. Oh, you care for your mom, bless you or something like that.

Doria Rainey: But you don’t know the struggles, the heartache, the pain.

Bill Kubota: Doria’s mom, age 78. Not a talker. At least with Doria.

Doria Rainey: Everybody wants to be appreciated when they do something for you, even if it’s just, you know, thank you or, you know, a big smile. A big smile will help a lot. She won’t even do that for the most part, but it’s been a struggle. You’re about to eat lunch, okay.

Bill Kubota: Detroit News survey found African-Americans make up the largest racial-ethnic group of caregivers in Wayne County. 45% and women make up more than 65%.

Rosa Hunter, Daughter & Caregiver: I’m the youngest. I’m number 6.

Bill Kubota: 68-year-old retired teacher Rosa Hunter in Harper Woods with her mother, also named Rosa Hunter.

Rosa Hunter: She’s 94 and a half. She’ll be 95 in July. Well, my mom was born in Birmingham, Alabama, and so she moved to Detroit and got married when she was 18. She used to be a dental assistant. She also was a counselor as well as a pastor.

Bill Kubota: Younger Rosa’s making a healthy lunch for mom.

Rosa Hunter: Seamos has 96 minerals and vitamins in it that our body needs. I keep track of my mom’s sleeping. Last night, she went to bed at 8:30 and she woke up at 6:00 in the morning. She slept nine and a half hours of sleep, which is so great.

Bill Kubota: Restless nights until Rosa started massaging her mom’s legs at bedtime. It’s vigilant in-home caregiving, keeping active, and avoiding a nursing home.

Rosa Hunter: She stayed by herself until she was 90 years old, but she got diagnosed with having dementia in her late 70s. But we didn’t notice a lot at that time, and she was still able to be independent, take care of herself, and cook for herself. The brain cells die, they shut down, they can’t do anything. And I said, Oh, I really don’t want that to happen to her. So I’m going to figure out a way and see if I can slow down the progression of dementia just by giving her healthy things, walking with her, talking with her, taking her places, listening to music, you know, just tapping into everything that I could about her body.

Dana Lasenby: And many people don’t understand mental health until it impacts them or somebody they love. And although we see it more now, which is probably the one only the one good thing that came out of the whole pandemic is that people are now talking about how critical it is for us to care for our mental health. But in our situation, we’re talking about people who are living with a serious disorder. And it’s chronic.

Hayley Harding: Why do you think, given that everyone’s going to be a caregiver or receive care at some point? Just statistically speaking, it will happen to almost everyone. Why do you think we don’t study it more? Why don’t we talk about it more?

Dana Lasenby: Wow. First thing came to my mind is stigma. People don’t want to talk about people in their families who need certain levels of care. And hopefully, I think I absolutely believe is getting better. The other thing is I think we don’t see ourselves in that space.

Doria Rainey: I don’t have a whole life. I have like a little bit of a life now, but I’m adjusting to figuring it out. You know, you would think, well, she wasn’t really close to me. She wasn’t… didn’t bond with me as a child. But now I’m caring for her. I’m doing all these things for her. So I did have an issue at first just mentally just taking care of her. So that was hard. For the most part, it’s a lot. You know, physically dressing a whole person that’s not helping. You know, she doesn’t help at all. She can walk, but she keeps her legs like this. When our physical therapist came out, this one was like a 45-degree angle, and then this one was 15.

So we have to kind of exercise them so it makes it hard to pull up pants and do everything because she’s not cooperating. Are you? You cooperating? You want to say hi, you want to talk? I have to learn little techniques and strategies. So I look at YouTube videos. It’s a young lady at my church. She took CMA classes, I called her over and asked her to show me how to turn my mom in bed and, you know, just show me little things so I can be more efficient.

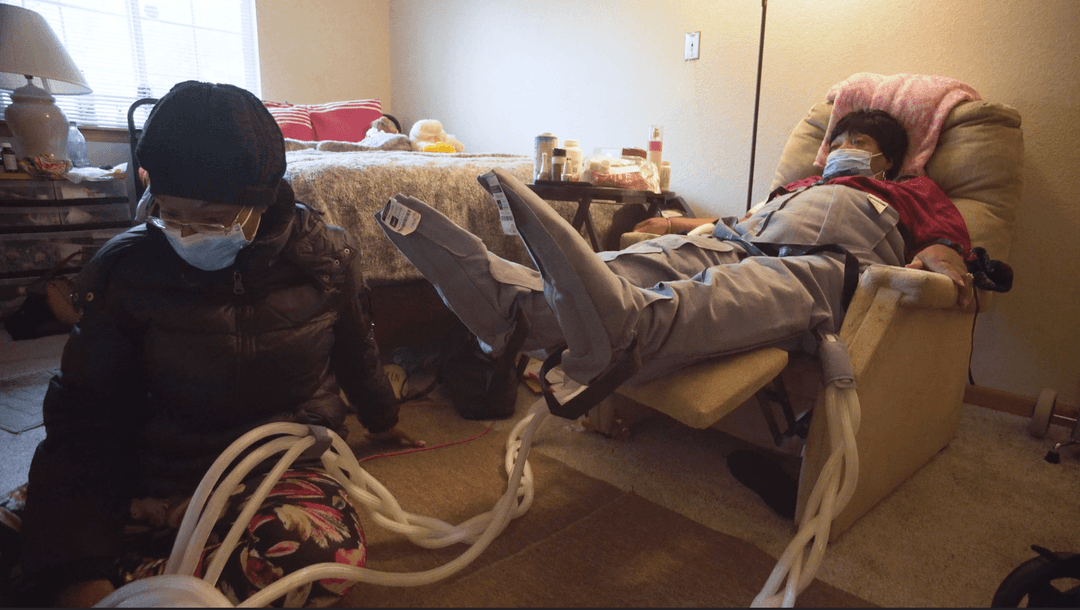

Bill Kubota: Back in their Gross Ile’s senior apartment it’s Nakia and Dorothy Gaithers after lunch routine.

Nakia Gaither: I don’t sit down. It’s nonstop until I go to bed, isn’t it Mom?

Bill Kubota: This outfit helps with blood circulation.

Nakia Gaither: You feel it now? Everywhere?

Bill Kubota: A Detroit News survey found 52 percent of metro Detroit caregivers have to pay out of pocket for caregiving materials. It can be hard to get insurance to cover outside help just so primary caregivers can take a break.

Rosa Hunter: They always look at the income. And so her income was higher than what was expected. So I couldn’t really get help there. But I thank God that my sister comes every Tuesday to get her and take her out to eat. And my brother, even though he has Parkinson’s, he can still be here present with her. And so he comes on Saturday so I can run my errands and do what I need to do personally.

Bill Kubota: As the survey found no surprise, women more so carrying the load. Doria Rainey has two brothers.

Doria Rainey: So I was like, okay, guys. You know I send them a text. Okay, guys, I need a break. Who can come and get mom or who can take her to their house or whatever. And I don’t know how to care for her. I don’t know who’s gonna help me and things like that. But for me, it’s like they just think that because I’m a female that I can do it, which I can, but they can hire somebody.

Bill Kubota: Nakia Gaither does see some compensation. It’s through Medicare where she clocks in as a caregiver.

Nakia Gaither: My hours are 29 hours a week. That’s what they have me on the clock. But as you see, this is more than 29 hours a week. She is under the Medicare Waiver Choice program under the senior alliance. They pay so much for a caregiver. I get 329 a week, but that’s her supplement income, not mine. For the supplement income that’s for groceries. I have to put gas in the car to get her to the store. So it goes for me, but it’s really for her.

Bill Kubota: Along with the spin classes, Gaither fits in some online food delivery work a few hours a week, if she’s lucky.

Hayley Harding: We know that more than a quarter of caregivers are working 21 hours plus a week, which is a full-time job in addition to whatever other jobs they have. We know that around a quarter of them are doing it by themselves. They don’t have other support. How do we make those kinds of things better for people when they’re alone? They’re doing their best and they’re working a lot while they’re doing this, though.

Dana Lasenby: I think natural supports have to be sometimes reimbursed. So you talk about natural supports in terms of, oh, well, your mom, you’re supposed to do that. Or you’re the daughter, you’re the closest family member to that person. You should do that. You have to do that. But we forget about all the other responsibilities a caregiver could have. And how do we find ways to help that person so they don’t have to work three, four, or five jobs to take care of that individual when they need the help that they need?

Rita Choula: Finding solutions as a family caregiver is the big question. Unfortunately, healthcare professionals and others make this mistake of thinking and taking for granted the role that family caregivers play, and thinking caring for someone just comes naturally. Well, you can care for someone and still need support.

Bill Kubota: AARP helped make a scorecard Ranking States by caregiving standards. Michigan is number 30. At the top, Minnesota and Washington.

Bea Rector, Assistant Secretary, Aging and Long-Term Support, State of Washington: Because we’ve really had an intentional focus on caregivers since 1989, and we’ve just been growing and evolving our program over that time.

Bill Kubota: Bea Rector’s with Washington State’s Aging and Long Term Support Administration.

Hayley Harding: What do you think Washington is doing well in meeting caregivers where they are?

Bea Rector: Well, I think we’re doing well in a couple of areas, like Paid Family Medical Leave Act that was enacted and began in 2020. That protects workers who need to take time off due to family caregiving to be able to do that up to 12 weeks and creates kind of a partial salary replacement for them to be able to do that so they’re financially secure while they’re caregiving.

Bea Rector: We also have the WA CARES Act.

Unknown Speaker 1: WA Cares Fund is a benefit you earn, like Social Securtiy.

Bea Rector: Which is a new long-term services and support insurance for working Washingtonians that will go into effect in July of 2026.

Unknown Speaker 1: And can help pay for services you may need, such as in-home care or home-delivered meals.

Bea Rector: And that will provide paid family caregiver support to individuals who are eligible for those services. We also have a very supportive legislature because we’ve been able to talk about the value of caregiving, but also the value to the state budget in investing in family caregiver supports.

Bill Kubota: In Washington State, caseworkers assessed caregivers’ needs, help solve their problems while running a campaign promoting caregiving as the work it really is.

Bea Rector: And basically, it says, you know, you call it going grocery shopping for mom. We call it caregiving. You call it helping Dad with medications. We call it caregiving. Please call. It’s okay to ask for help.

Bill Kubota: For the caregivers here we talked to, they’re making their way through. So far.

Doria Rainey: I think she’s still living a good life. She’s not in any pain. She’s not in and out the hospital. So I thank God for that, you know, her quality of life, even though she’s not really doing anything, is still a good quality.

Rosa Hunter: I mean, she’s still here today and she’s still asking questions and she can feed herself. And she’s not in a diaper at 94. And people are surprised. Even the doctors are. It’s just so many things she can do.

Bill Kubota: Rosa Hunter’s success with her mom, maybe it’ll rub off on some other East Side seniors. Rosa finds time to lead some exercise classes in Grosse Pointe Farms.

Rosa Hunter: And I do cardio, but I also include foreign language, sign language, and sing-along songs at the end. Things that are good for your mental health as well as your physical health.

Dorothy Gaither: I’m 72 and I thank God for if it. If I didn’t have this walker, right now I would volunteer at least two days a week because I love caregiving.

Nakia Gaither: She is able to walk. I have to help her get in and out of the tub. And sometimes I have to help her get up out of bed. But she’s not bedridden. Excuse me, one second. Let me check on her machine.

Hayley Harding: In Washington State and in Minnesota, they have a whole program dedicated to just having a social worker or caseworker check in with the caregiver and say, how are you doing? How can we connect you with resources?

Dana Lasenby: I love that.

Hayley Harding: Just really like empathetic policymaking. Do you think we have that space here too?

Dana Lasenby: I love it, I love it. I would love to explore that more because I absolutely think that does make a difference when you care about the direct care worker and how do we put them first and make them know how critical they are. I think they know. But money talks.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel & Don’t miss One Detroit Mondays and Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @DPTVOneDetroit, and Instagram @One.Detroit

View Past Episodes >

Watch One Detroit every Monday and Thursday at 7:30 p.m. ET on Detroit Public TV on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel and don’t miss One Detroit on Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 9 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @OneDetroit_PBS, and Instagram @One.Detroit

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*