A Michigan deportee adjusts to Mexico. ‘I don’t wish this on anybody’

Oct 3, 2017

by Chastity Pratt Dawsey

What happens after deportation?

It’s a question on the minds of some 800,000 young immigrants known as “Dreamers” who aren’t U.S. citizens but were raised in the country and may now face deportation as Congress debates their fate.

It’s reality for Maria Juarez, 23, who was raised in the U.S. ‒ the only country she knew ‒ but now finds herself in Mexico after her deportation in May.

Bridge Magazine was in Mexico last week along with its reporting partner, Detroit Public Television, to continue telling the story of this young woman and other deportees who find themselves strangers in lands that are now their home.

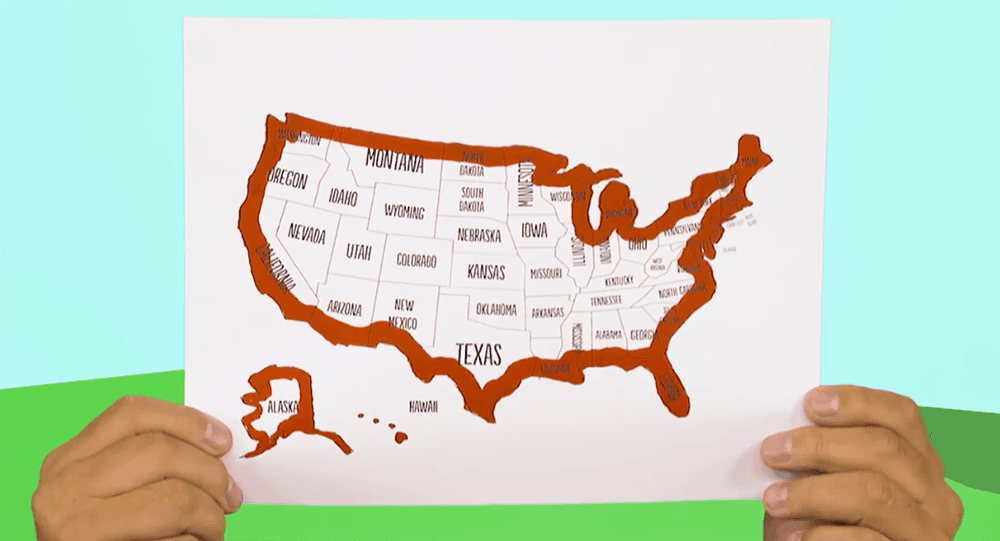

Juarez spent her life in the U.S. after her mother took her from Mexico to California when she was 8 months old. Though she had a Social Security card, paid taxes and married a U.S. citizen, Juarez was an undocumented immigrant and deported. The reason: Though she fit the profile of dreamers brought to the U.S. as children, she got in trouble as a juvenile in California for stealing two cars, making her ineligible for dreamer status.

But with more than 6,000 dreamers awaiting their legal fate in Michigan, Bridge wanted to see how young people like Maria Juarez, raised in the U.S., fare after deportation.

She now lives secluded in a relative’s small compound in Maravatio del Encinal, a dustbowl town in central Mexico that is the beset by warring gang cartels.

“I don’t wish this on anybody,” she told Bridge.

“This is a very, very drastic change in my life. … People, food, water: Everything is completely different (here.) I’m afraid to go outside.”

Juarez left behind a son in Detroit, who celebrated his second birthday while she was gone, and a husband who is awaiting a stem cell transplant to fight his second bout with leukemia.

Roughly 800,000 U.S. young people have “Deferred Action For Childhood Arrivals” status, a two-year renewable pass to work in the United States. But the program is set to expire in March unless Congress passes a new law.

Though Juarez isn’t a dreamer, her story is illustrative of the experience that might await young people like her. Juarez says her uprooted life remains a shock to her soul.

“I worked hard in Detroit, so hard I barely saw my family,” Juarez said in an interview last week week in Salvatierra, a small city near her town about 170 miles northwest of Mexico City.

“Here, I’m nobody. I’m scared.”

Bridge Magazine is reporting on her life, and the lives of others, in Mexico, as well as the families she and others left behind in Michigan. Our report, along with a planned 30-minute special on Detroit Public Television, will air later this year.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @detroitperforms

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*