Communities of color break down stigmas, prioritize self-care for Mental Health Awareness Month

May 2, 2023

May is recognized as Mental Health Awareness Month, a time to raise awareness about the importance of mental health, the impact of mental illness, and an individual’s overall well-being. This year, “American Black Journal” is focusing on how mental health impacts communities of color, particularly African Americans.

According to the latest statistics from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), one in five adults experiences mental illness each year. The data also shows that African Americans are 20% more likely to experience struggles with their mental health compared to the general population. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the situation, leading to heightened stress, anxiety and depression.

The good news is that there’s a growing awareness about the importance of self-care and seeking help when needed, and there are efforts to break down the stigmas surrounding mental illness in communities of color.

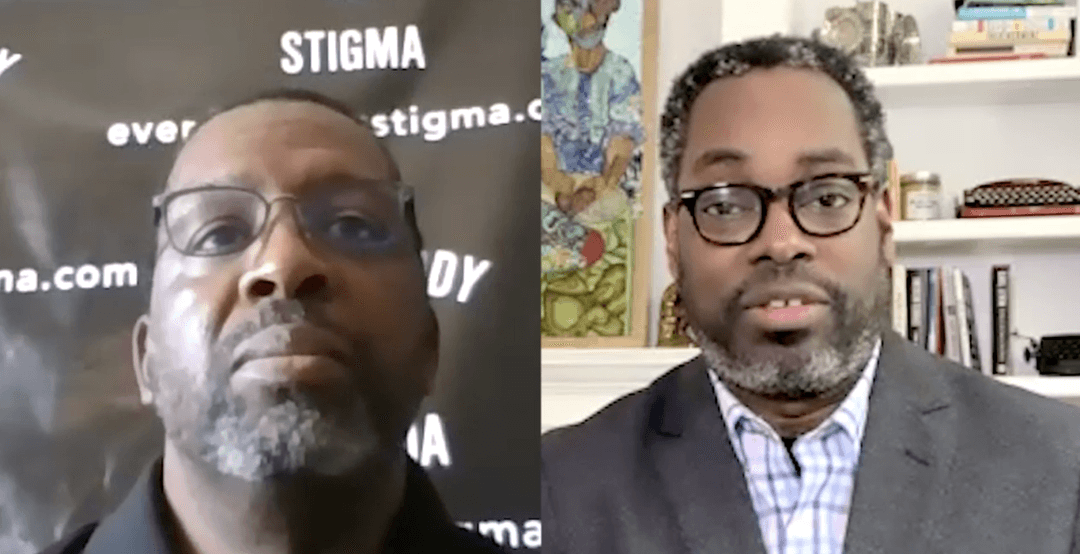

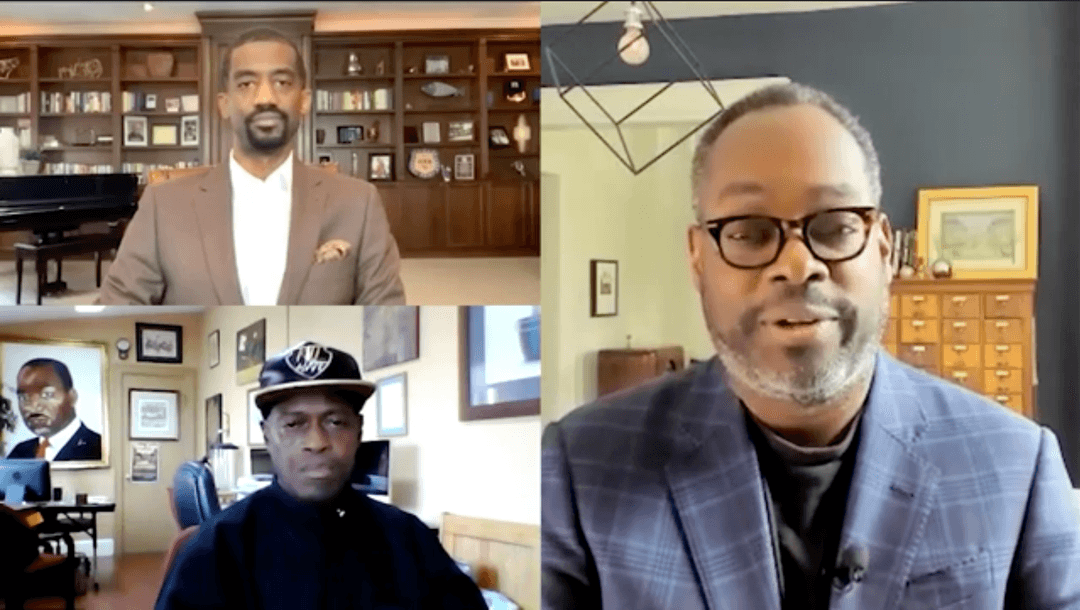

In recognition of Mental Health Awareness Month, “American Black Journal” host Stephen Henderson talks with two mental health representatives, CNS Healthcare President/CEO Michael Garrett and Judson Center Director of Integrated Health Services Jamila Stevens, about the stigma surrounding mental illness in the Black community, the increase in the number of young people experiencing mental health struggles during the pandemic, and how you can perform a mental health self-check on your own.

Full Transcript:

Stephen Henderson, American Black Journal, Host: I want to start off talking about this moment and the sort of difference that we’re seeing because of the pandemic with mental health. I think this took a very difficult subject and made it even darker. Jamila, I’ll start with you.

Jamila Stevens, Director of Integrated Care Services, Judson Center: I definitely agree, Stephen. And I think one of the things that impacted is, is the isolation one and than two just this notion of literally living through a pandemic where grief and loss and trauma are at the forefront. Definitely impacted everyone when it comes to depression, anxiety, fear. Not even feeling comfortable if you could interact with your family members. A fear of losing people. So it definitely has escalated symptoms in individuals who already had a diagnosis. But then secondly, it caused other people to may have a diagnosis that necessarily didn’t wouldn’t of have had one prior to the pandemic.

Stephen Henderson: You know, the pandemic is technically over. I mean, at least much of the disruption of the pandemic is behind us. And so I think that is also telling people in some ways that the problems of the pandemic are not necessarily with us anymore. And I and I think with mental health, that’s just not true, that just because we’re no longer social distancing, just because there isn’t the kind of loss and grief that we were experiencing doesn’t mean that the effects on our mental health have gone away as well.

Michael Garrett, President & CEO, CNS Healthcare: It’s not even close. The effects of the pandemic are still ongoing. We’ve all seen the news that during the pandemic, the stress on the primary health care system, the emergency rooms, the overcrowding of hospital beds were at the forefront of people’s minds.

Michael Garrett: But there’s been kind of a delayed reaction when you talk about the behavioral health care impacts of that. We are have started, we started seeing the increase in demand probably about a year, eight, eight to 12 months after the pandemic started, where the behavioral health increases started rising exponentially. We have more people needing behavioral health care treatments than we have the capacity to treat right now. So as the previous guest talked about, the issues of loss and depression and isolation have been on the rise. Substance use disorders have been on the rise as well. We’ve been seeing a lot of people come to our doors requiring treatments for those. So no, while the pandemic is over, we’re going to feel the effects of that for many years to come.

Stephen Henderson: So I want to talk specifically about children, our kids, and the ways in which the pandemic made mental health more of an acute issue for them. In some ways, I think it’s kind of an obvious thing to have happened, given the disruption to them. But again, I’m not sure that the kind of attention that the issue needs is being put on them. Jamila, tell us about the kind of things that you’re seeing with children that is different from the rest of the population.

Jamila Stevens: I think one of the things that we’re seeing here at Judson Center as we’re providing services to our community members and we also provide services in the schools, is this disruption in regards to development. So one of the things we have to remember is that as some of our younger kids, even kindergarten and younger were starting their development in school, they were isolated. And part of child development is peer-to-peer interaction.

And so one we’re seeing as the kids are returning to school, their sensory, their sensory issue, they’re overly sensitive. There’s an overabundance of this interaction of individuals that they weren’t accustomed to, which is then causing them to have a reaction in behavior which, in some instances may look like negative behavior, but it’s really anxiety. It’s really this impact of being thrust into an environment that they did not really have the chance to step into in a traditional way.

So that’s at our elementary younger age. As the kids get older, similar to what Michael was stating, grief and trauma, there’s a delay in that process. So you’re in shock. And now those symptoms of grief are presenting themselves where there is a higher rate of suicidal ideation, a higher rate of depression.I’m getting referrals every day and the ages are getting younger and younger, for kids who are experiencing those intrusive thoughts and those internal responses to stress. Now, as a at a later time with the loss and grief that they are experiencing was a year or a year and a half ago.

Stephen Henderson: Yeah. Yeah. Michael, what are you seeing and hearing about young people’s mental health with the pandemic?

Michael Garrett: It’s the same thing. When you talk about suicide rates, particularly among Black people between the ages of ten and 24. The suicide rates or the people who have at least contemplated or tried suicide are kind of through the roof right now. And it’s a very disheartening and disconcerting thought. But it’s something that we see with the people that we intake every day and really have to get very aggressive in our treatments and our interactions and our engagements with those individuals. Some of the programs that we offer to offer those mental health interventions a lot sooner than maybe otherwise we typically would have. And particularly among Black females

It’s one of the groups that we’re seeing a particular rise, you know, and that requires suicide interventions in that particular age group. So we’re doing everything we can on the front lines to try and get these people into treatment, get them into some of our suicide prevention programs. And the ones that we have been able to enroll and the ones to follow the treatment guidelines, we’ve been very, very successful, you know, in preventing those adverse outcomes that come along, you know, with some of those struggles.

Yeah.

Stephen Henderson: So I want to talk about how we know and how individuals know when they should be seeking help, when they’re having, you know, the kind of problem that, you know, professional care environment would help with. But I also want to talk about that in the context of our community, the African-American community, where there is still a bit of a stigma, you know, associated with mental health care and the idea of raising your hand and saying, saying you’re having a hard time. What should we be looking for and how do we get people to engage? Jamila.

Jamila Stevens: I think the first key is that mental health services is not for a specific community or specific diagnosis. Most individuals have a mental health benefit for their insurance, and that means that it’s accessible to all. So I think there’s a misconception around when to seek services. Our role is, is when people come in is to determine what level of care they need based on what they’ve experienced. So that’s the first step. Taking away the stigma of you have to have a particular type of severity in order to receive mental health services, which is could and consist of therapy as well as medication, as well as support services, case management services, things like that.

So one, what that, what those services entail and that is accessible to all. I think one thing that is key to look for specifically in our community is that if you begin to disengage even more and you’re you find yourself exhausted more than usual, if you are having what I said stated those intrusive thoughts, just random thoughts coming through your mind, don’t ignore those. Pay attention to them because over time thoughts could turn into action. And then also, if you’re noticing that your temper is changing. We… Part of anxiety is that sort of adverse reaction to things, being angry or aggressive, we assume that we’re upset or it’s just a bad day. But you could be overstimulating and your anxiety could be increasing.

Stephen Henderson: Michael, how do we identify when we need help and how do we get more African-Americans to be comfortable with that idea?

Michael Garrett: African-Americans, this is an issue that’s unique to African-Americans. Let me first state that. In predominantly communities of color, whether it’s Latino Americans, Arab-Americans, or Asian-Americans, the stigma or for people, for people who require mental health treatment. People seeking mental health treatment is extremely high . Fear that they’re going to be labeled crazy by their friends and loved ones is still out there. One of the encouraging signs that we’ve seen is that the younger generation, particularly people who are under the age of 21, have been far and college-aged individuals as well have been far more receptive to being open about their mental health struggles, engaging in treatment and seeking out that help.

So generationally, it is changing. But anecdotally, our aunts and uncles and grandmothers and grandfathers, they’re still on that same page of, you know, just, you know, deal with it, walk it off, it’s going to be okay. We don’t talk to people about our problems. That’s not that’s not the path forward that we need to do. Encouraging signs have been that the primary care community has started engaging in things that can help get more people onto treatment. If you’ve been to a physician in the past few years, oftentimes they’ll ask. Have you how are things going at home? Have you had any thoughts or any struggles with regard to stress, or have you had any thoughts of harming yourselves or others?

Your primary care doctors are now asking those questions. I think we all benefit from what I call a mental health checkup every year. Just like you go to your primary care doctor to make sure that your blood sugar levels are okay, your cholesterol is okay. Talk to a therapist or a psychiatrist once a year. You may not be having any issues that you may be aware of, but just sit down, talk to them. If they say, okay, everything seems to be fine with you. Great. See you next year.

But if they detect something that may require a follow-up visit then handle that, you know, at the appropriate time. But and as Jamila talked about, most commercial insurances have a mental health benefit to allow for that. The second thing that I would encourage people to do, and this has more to do with people who are resistant to treatment, who, you know, their friends and family could be suffering from something obvious in the behavioral health care space. Be a buddy to your friend. Okay. And particularly males. Okay. I’m speaking to the guys now because, you know, we don’t like to go to the doctor unless our arm is literally about to fall off or something like that. If you have a buddy, you know that he’s going through something, say, hey, look, you know my man. You know, I know you’ve been having some difficulty and things.

You know, maybe when you’re having lunch or dinner, you know, at a sports bar or a sporting event and say, hey, look, you might benefit from talking to somebody. And as a matter of fact, for your first appointment, I’ll go with you. I’ll drive you there. I’ll sit in the lobby while you’re in there talking to, you know, the mental health professional. And, you know, after we’re done, after you’re done we’ll go, you know, we’ll go to a ballgame or something like that.

Having that level and that kind of support from a trusted person in your life can make people feel far more comfortable engaging in mental health treatment than just saying, hey, you know, I know something is wrong. You need to go see somebody right now. Be a true friend and help them through that process.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram @amblackjournal.

View Past Episodes >

Watch American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @amblackjournal.

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*