Detroit’s Black Catholics Continue Efforts to Rebuild Community After Population Decline

Apr 27, 2022

Detroit’s Black Catholic population isn’t what it used to be. What was once a thriving religious community here has dwindled over the years.

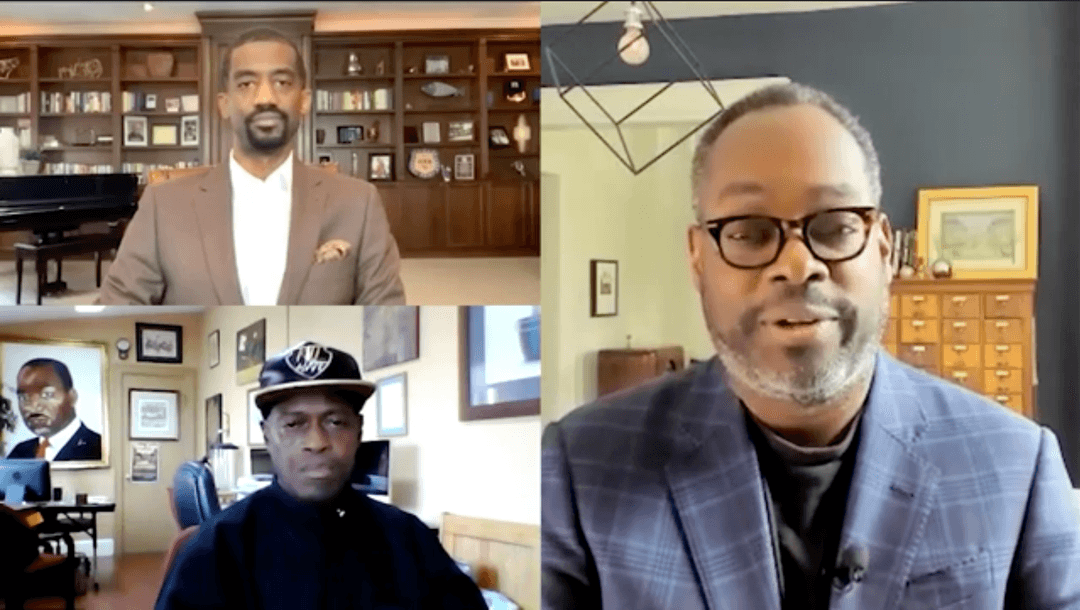

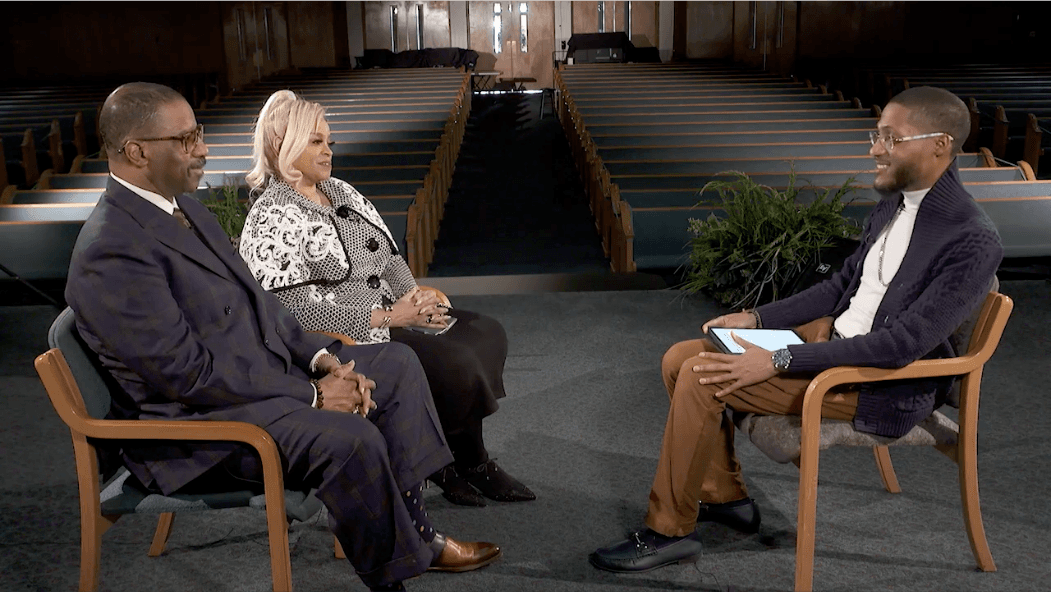

Host Stephen Henderson sits down with University of Detroit Mercy President Dr. Antoine Garibaldi and Vickie Figueroa, the associate director of cultural ministries at the Archdiocese of Detroit, for a discussion about Detroit’s Black Catholic parishes, including the dwindling population of Black Catholics and what efforts are being made to rebuild the community. Plus, they talk about the state of Catholic education in the city.

Full Transcript:

Stephen Henderson: So, Dr. Garibaldi, I’m going to start with you. Of course, you’re the president of U of D Mercy, the largest Catholic institution, really, of higher ed in our state. And it’s important, I think, that U of Mercy is in Detroit. It’s been in Detroit since the beginning, and that gives it a special role, I think, when it comes to the African American community that has grown up here in Detroit, that become the majority. It’s impossible to talk about, I think black Catholicism, it’s impossible to talk about Catholicism in the city of Detroit without talking about U of D.

Dr. Antoine Garibaldi, President, University of Detroit Mercy: Right, well, I certainly think so. And having come from New Orleans, where my hometown was, and some of the priests who actually educated me and I was a seminarian as well, came right here from Detroit. They worshiped at, they were pastors at St George’s, as a matter of fact.

And so earlier in the last year or later in last year, when I gave my talk about the role of Detroit in terms of black Catholic history, it was a delight to be able to do that, to know that there were five primarily black parishes here between the 1914 and really up until the present day, that really had a lot to do with the many black Catholics who came from the South, which is where the majority of the 3 million African-American Catholics are located. So, being here at the University of Detroit Mercy has really been a very, very special privilege because of the role that they played right here with the community.

Stephen Henderson: There’s also been times when the U of D community has played a key role in the struggles that African Americans have had linking arms with the African-American community to fight for equal rights and justice.

Dr. Antoine Garibaldi: That’s true. And, you know, so much of that history and, you know, I refer to my years in the seminary because I was in the seminary between 1964 and 1972. And though I was in Newburgh, New York and Washington, D.C., I often used to think that the seat of a lot of the African American Black Catholic movement was in Washington, D.C., but in fact, it was right here in Detroit. Because, as I say, often 12 days after the assassination of Dr. King in 1968, was the first meeting of the Black Catholic Clergy Caucus right here in Detroit.

And a year later, the Black Sisters Conference had its national meeting as well, too. And the fact that the black secretariat, the first black secretariat in the United States was here in Detroit makes it even more special. And the fact that the Jesuits and the Sisters of Mercy right here in this neighborhood, you know, really reminds us of about a lot of history that many people are not aware of here. And many of those people who experience it, unfortunately, have passed on. Because I have four sets of cousins who came here from New Orleans in 1944, and they’re in their late 80s right now and could tell me about a lot of that wonderful history.

Stephen Henderson: So, Vicki, I want to talk about the history of Black Catholicism in the city, but I kind of want to start off with a little bit of a amend. I grew up here in the 70s and 80s in Detroit, and was part of the Catholic community, mostly through schooling. And I feel like, just like much of the rest of Detroit, we just have less of what we used to have when it comes to Black Catholicism and Black Catholic parishes. You know, just as the city has kind of shrunk, this community has had its challenges sustaining itself.

Vickie Figueroa, Associate Director, Cultural Ministries Archdiocese of Detroit: Right, that is a very good observation, thank you for bringing it up. Especially, especially during the eighties when a lot of the city parishes closed, you know, a lot of Black Catholics left. Could not find a parish that they felt comfortable in or just decided to leave the Catholic Church altogether and go worship somewhere else. Or an even worse tragedy, not worship at all.

So, the closing of the parishes, especially in the year of 1989, did have a profound effect on the Black Catholic community. One of the things that we try to do with Black Catholic ministry is building relationships with the parishes, the black Catholics, who are still, you know, faithful to the Black Catholic community, and then do outreach to our brothers and sisters who have left and are joining us in the pews. And we try to do this through outreach, through evangelization, through conferences, through leadership development programs, through community events. So, whatever we can do to kind of rebuild our Catholic community, our Black Catholic community, is pretty much what my office has been charged with.

Stephen Henderson: And so, what does that look like? Rebuilding that community, and that is also happening alongside rebuilding the community more generally here in Detroit.

Vickie Figueroa: That’s correct. What this looks like is, especially in the past three years, since I’ve been part of the Black Catholic ministry in Detroit, what we’ve done is we’ve kind of like revamped and revived ourselves. Last year, we put together the kind of an advisory council of about 10 to 12 black Catholics, some who have only been with the church a little bit or for a few years, who are converts and others who have been with the church for many years and have generations of family and relatives who have been part of the Black Catholic experience in Detroit.

And we sat down and said, okay, considering the closing of the parishes back in the 80s, considering the great migrations of the 30s, 40s and 50s, considering the closing of a lot of Catholic schools, and considering where we are now in the, “Unleash the Gospel Movement”, that the Archdiocese is promoting out in our community, who are we as Black Catholics and where are we and what should our priorities be to rebuild ourselves? So, they came up with many priorities, but we narrowed it down to 6. And those include building community, it includes building faith, Catholic schools, you know, women’s initiatives and making sure that our black Catholics don’t get lost in, you know, the process of reorganizing some of our parishes called families of parishes.

So, we put together what our priorities are because, you know, along with the pandemic and then some of the social justice issues of a few years ago with, you know, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, it took a toll on the black community because one of the hallmarks of Black Catholic spirituality is communitarianism. It’s community. It is being together. And when you take that away from us because, you know, parishes had to close to keep people safe, you know, that takes a little bit of an impact.

Actually, it takes a pretty big impact on black Catholics and part of our spirituality, because it’s always to be together and to love upon each other. So, we took all of this into consideration and said, okay, these are the priorities that are going to help the Black Catholic community to heal again. And the number one priority is community building, which is that healing process. So that’s kind of what that’s gonna look like right now.

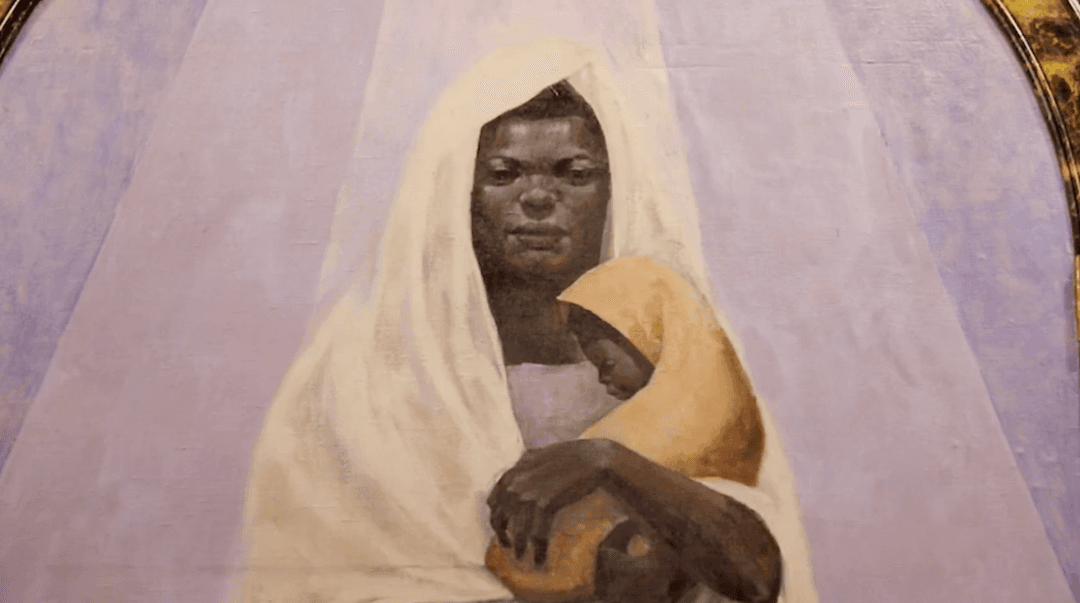

Stephen Henderson: I also want to give you a chance to look at a particular parish that I feel close to, Charles Lwanga, which, was St Cecilia’s. It’s around the corner from the house where my family lived when I was born over on the west side. And that parish is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. But I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the fact that the depiction on the wall of the altar of the Black Christ there, is and was this really pivotal moment in the celebration of Black Catholicism in the city. It was painted the year after the 67 uprisings as a way of demonstrating that the city was changing, becoming more diverse, and so was the black church.

Vickie Figueroa: Yes, definitely. One of the things that’s very important in Black Catholicism, in the Black Catholic community are images of black Catholics and black spiritual figures who look like us. It’s hard for us to be something that we cannot see. So when you have images like the one at Saint Charles Lwanga, which is one of my favorite places for prayer, because they have an absolutely wonderful pastor who’s an outstanding academic theologian and just a fabulous preacher.

His name is Father Ted Parker, one of my favorites ever. You know, when you have that imagery, it really brings your face alive. When you see the black Jesus, when you see the black Madonna, when you see our six saints or six men and women on their road to sainthood, such as, you know, Sister Thea Bowman, Mother Henriette Delille, Pierre Toussaint, when you see these folks, you say they are Catholic, they are black Catholic, I’m a black Catholic and I wanted to aspire to be like them and I can find comfort in that black image that’s before me.

Stephen Henderson: Dr. Garibaldi, I wonder if you can talk more about the role that the university is playing now in celebrating Black Catholicism, the presence of black Catholics in the city, and particularly in that neighborhood where the university resides.

Dr. Antoine Garibaldi: Yeah. Well, Stephen, two things. First of all, I need to mention my parish, my wife and I go to Gesu. So that’s obviously a place that is very special to many people for many years and people come from miles away in order to worship Gesu. But one of the things that we started this past year, was to have an annual lecture celebrating Black Catholic History Month, which is in the month of November. And, you know, there are many places around the country that have been celebrating this for a very long time. And I was fortunate to be able to kick it off this past November.

By doing it, I shouldn’t say I was fortunate enough, I was forced to do it. We do have some people in mind, but they thought it would be a great idea if I did it, but it is one of the ways in which we need to highlight and celebrate the role that Black Catholic history has played here in the city of Detroit. So, by doing this lecture series, it’s been a, it’s a way to kind of bring people together. There are lots of young people and people who are of our age who would not have known about that history because they were not around. And when you mentioned people like Sister Thea Bowman, who was a dear friend of mine as a young seminarian, and even Bishop Moses Anderson, who was one of the early African American bishops in this country, he was only the seventh black bishops in the United States in the mid-70s.

There are a lot of people who have been here and who played such an important role. And we really want to spend more time talking about that history and also talking about what we’re doing now. And Vicki’s been doing a great job throughout the archdiocese, but we cannot let that history pass. You know, when I read that Pew Research Center study talking about the fact that black Catholics, for the most part in this country, do not go to parishes where they are the majority. Well, before the 1970s, they had no other choice than to go in the south, in particular, to parishes that were primarily African American because segregation existed.

Segregation existed in New Orleans when I was in school. Before 1965 I couldn’t go to high school where the student body was primarily white. But those things have changed, and it’s important to really remind people about that because it shows the strength of African American history and the African American faith. My mother was raised Catholic, my father was AME, and my father was married to my mother for 20 years before he converted.

So, but all 8 of my siblings plus me, were educated in Catholic schools, in the high schools and fortunately, most of us were able to go to college at Xavier in New Orleans, for example. But that’s important history because it shows the strength of African American Catholicism. And Cardinal Gregory’s elevation last year at a Cardinal, we all said it’s about time. There were lots of great candidates, but he’s a wonderful man, a convert to the faith as well, and a great example of just showing how, you know, that faith has been so secure and so strong for so many years.

Stephen Henderson: Vicki, I want to give you a chance to talk a little about schools as well. Like I said, the 70s and 80s, that was a real option for black parents and an alternative, I suppose. It’s less so now. Is that, is restoring more of that, I guess, one of the focuses that the archdiocese is really embracing as we try to regrow the city?

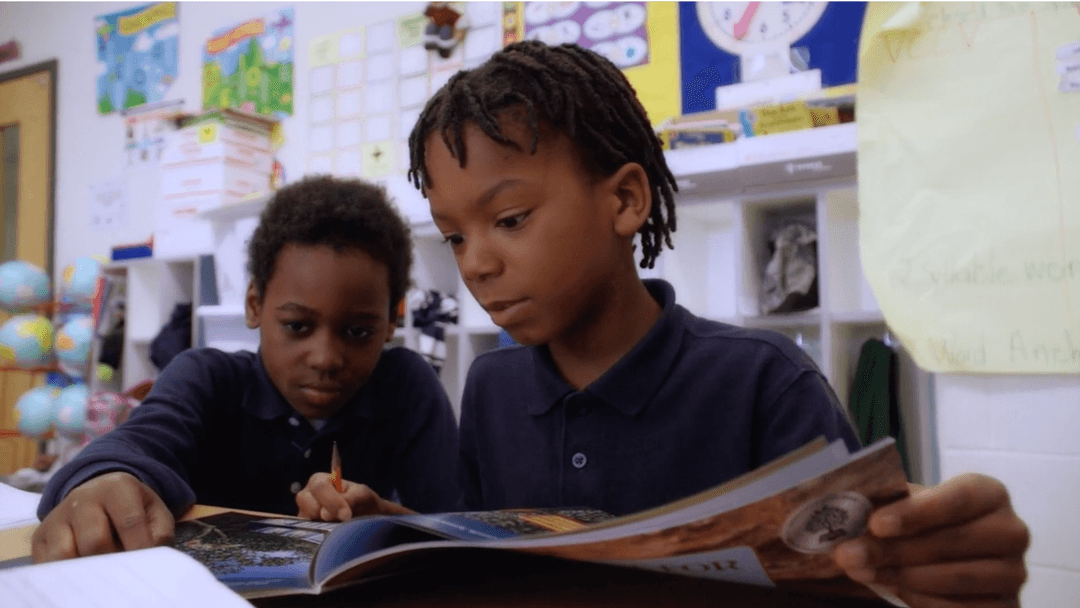

Vickie Figueroa: I believe they are. They are looking at special initiatives to make Catholic education available to all families who want access to it. So, that is one of the things they’re going to be working on. And you’ll hear more about that coming in the near future. Catholic schools are dear to my heart. I’m a transplant from Ohio, I’ve been here 25 plus years, so I’m almost a Detroiter. But I went to Catholic schools, and it transformed my life.

You know, it empowered me to believe in myself and change my life, you know, go to college, become part of the middle class. And this is something that Catholic schools do very, very well, is that, you know, they offer high-quality education, and they give children in the inner city, African American children, the chance to improve their lives, change classes so to speak, and then improve the lives of others. Because when black children go to college, they become lawyers, they become doctors, they become nurses, educators.

So, they have kind of this multiplying effect on the generations coming up after them. So one of the things that we’re going to do with the Black Catholic Advisory Board, one of the priorities we are looking at, of course, is youth, and how can we encourage more African American youth into our Catholic schools in lieu of there’s a lot of competition out there for those students between, you know, charter schools and public schools and other schools getting the attention of our kids.

How do we create a product or advertise or market a product that parents will see as superior in terms of faith education and academic education that will prepare their kids for college? So still a viable option, but we still have some work to do.

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram @amblackjournal.

View Past Episodes >

Watch American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @amblackjournal.

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*