Collection of Horace Sheffield, Jr.’s Archives Coming to Wayne State University, WCCCD

Feb 15, 2022

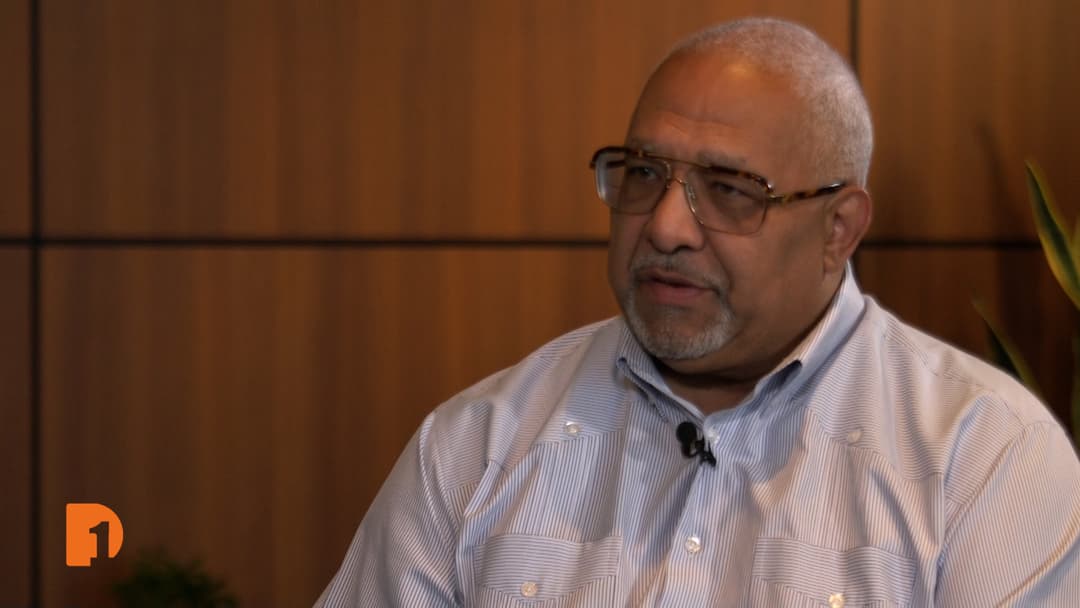

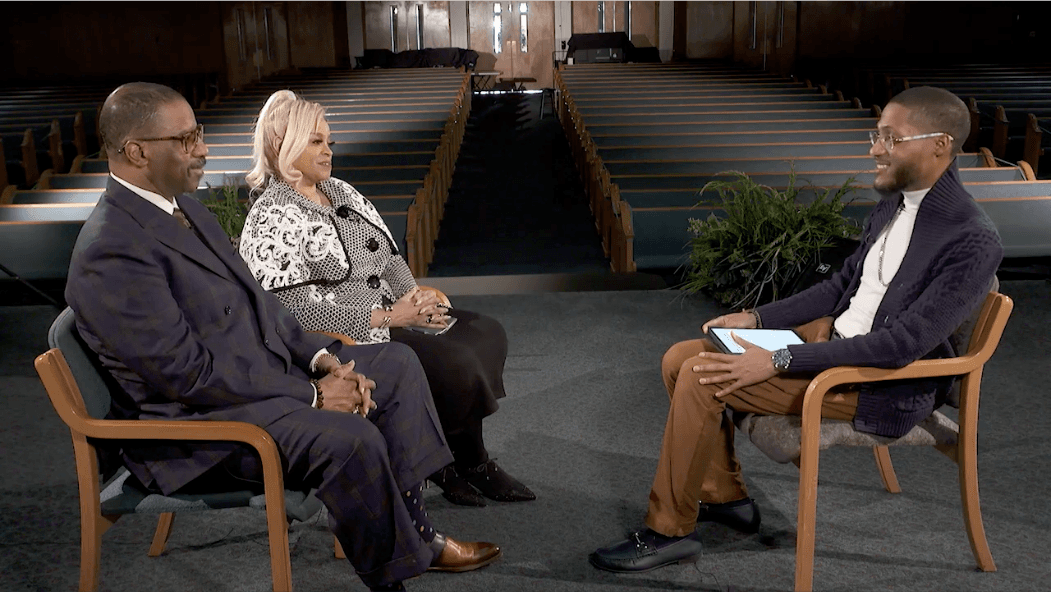

In celebration of Black History Month, host Stephen Henderson explores the legacy of Horace Sheffield, Jr., a trailblazer in the African American labor union movement. Stephen talks with the late Sheffield’s son, Rev. Horace Sheffield III, about the influence and impact his father had on the trade unions during the civil rights movement. Plus, Sheffield III talks about upcoming plans to house thousands of items from his father’s archives in a massive collection at Wayne State University and Wayne County Community College District.

Full Transcript:

Stephen Henderson: Excited to talk to you about your dad and the work that you’re doing to preserve his archives and his legacy. But I figure we probably ought to start with just a simple recitation of who your dad was, what he did and why he’s so important. Not just to the legacy of labor here in the city of Detroit, but especially to the legacy of civil rights. He really was something else.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III, Executive Director, Detroit Association of Black Organizations (DABO): Well, you know, and my dad, much like me, was not a self-promoter. You know, he was a race man. And in that generation, as you know, because your family is a part of that. These are people who deferred their own aspirations for future generations to experience what they never had an opportunity to.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: So it wasn’t about him getting the job, it was about opening the door, making sure certain other folks came in. But I think Willie Felder opened my eyes to who my dad was at his 100th birthday celebration and told me he was in Birmingham, Alabama. And A.G. Gaston who was a millionaire invited my dad down and my dad brought Thurgood Marshall with him.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: And they were having a meeting because these Black veterans who have come back from the war were being discriminated against, not able to get the, you know, the veterans loan. And so, he said, when my dad walked in the room, everybody knew who he was and knew that things were about to get started now.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: So my dad’s history is this. He, by the way, was Vice President, of Negro American Labor Council on A. Philip Randolph. He and Bayard Rustin served in that same capacity. Both of them were the staff organizers of the March on Washington for jobs in the war industry and of course, was the first person to bring Dr. King to Detroit. What people don’t understand is the success of the civil rights movement because you have Black labor organizers.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: Also, one tidbit is in his archives is that I discovered that he was the first person that they asked to be mayor to run as a Black mayor and my dad loathed politics. So it was very interesting that my daughter would become president of the council. But one good example. Five plus one, they went down and met with Mary Annie of Van Antwerp because of police brutality. The Big Four and all those things.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: And if you read B.J. Whittak’s book, you know that they brought the Klan here. And Charles Bowles almost won the mayor’s race in the 20s to discourage the growth of the Black population. And the police took on that mantra. And when they went down and met about what was happening, they said, that’s what we do. It’s in my dad’s archive.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: And what did they do? My dad came back to TULC had a big meeting and organized a slate called five plus one. The one was Jerry Cavanaugh and five Liberal Council and they won. They beat the UAW. They beat the white power structure. And that was a powerful moment in the history of TULC and Black trade unionism, which my dad was a part of.

Stephen Henderson: You know, just hearing you talk about those things, those events, you know, those moments in history, you can connect so much of what we see and experience today in Detroit to those moments that things are the way they are for us, in particular in the city because of those things that your dad and those other folks did.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: So what’s interesting is the same person who did Daisy Bates and Robert Kennedy and Jackie Robinson’s archives. We spent $90,000 dollars digitizing this and kind of tongue in cheek. The white guy says, you know this is one of the best collections. He didn’t want to say period, you know, but really, my dad had already annotated everything. I mean, back to a pamphlet he wrote with a pseudonym called Unite regarders encouraging Black workers to join the UAW, which my grandfather did until after it was accepted by the, you know, the collective bargaining agent.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: My grandfather thought that Henry Ford was the second coming of Jesus Christ. But my dad saved absolutely everything. And what’s important to me about all of this is that if I, you know you have family members, for example, that were in the trade union movement right, you can literally pull up people’s names, people that folks everyday people don’t know like.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: Ann Jones or, you know, George Cherry. I mean, and you will find information that my dad has. I know I’m running my mouth, but I’m so excited about this. But one of the most important pieces that I’ve read recently about where my dad took me where I was able to connect the dots was when he came home from King’s funeral, had to walk behind his coffin and an African-American trade unionist were absent from Memphis. And some of them were absent from the funeral because the white unions had turned against Dr. King because of his stance on the Vietnam War.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: And this five-page letter my dad wrote to Black Trade Unions asked the question. When are we even as a part of white institutions not going to be afraid to stick up for our own interests? They stuck up for theirs and make us bow to theirs. When are we going to make them bow to ours?

Stephen Henderson: So I know you’re doing this work now, trying to preserve his legacy and his archives. But I want you to talk just a little about growing up with your dad. I mean, this was your dad. He wasn’t just a civil rights activist. You know, this was the man who raised you. Talk about the things that you believe and the things you work on today, that were influenced by growing up in a household with him.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: Well, you know, my dad’s favorite question he asked in any meeting that he was organizing for an issue was what’s the difference between a pile of bricks and a cathedral? And no one would get it. He’d always say an organization the bricks are organized. So one of the things I got out was, by the way, this humongous movement. I mean, the social upheaval and all that you saw happen. I was there in that cauldron and that crucible.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: I mean, I watched Dr. King speak. You know, I went to Walter Ruth’s funeral. I mean, these are things that I experienced. And I asked myself I’m like the day when people would Tik Tok it and Instagram it and Facebook it. I asked myself, why? Why was I providentially placed in this era to be exposed to these people and to know them by name? You know, sleep in King’s House and all that. And I came away with it that I was to carry on the legacy of selfless service.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: My dad said the true measure of a person’s life is not how much they have, but how much they give. And I really think they came home in ’63 when we went to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and Lyndon Johnson received my dad and my sisters and I at his house, and my sister swam in his swimming pool as my dad met with Lyndon Johnson.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: And I didn’t come out of there thinking, Oh my God, I’m somebody, you know, look at us. I came away from it knowing that my dad was a pivotal, pivotal person in the movement for Civil Rights and that this blue-collar worker, he was a blue-collar worker. My grandfather had a fourth-grade education, came out of the foundry at Ford, organized workers, and his they called him a champion of the working poor and blue-collar workers that took him into Lyndon Johnson’s front room and was known by him and by name.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: And by the way, I got an interesting story about Lyndon Johnson. It’s in his archives you want to hear. And it was timely because Aavin Cone wrote this and told me it’s in the archives that Lyndon Johnson called my dad. He was the floor general at the convention and asked my dad not to seat the lady from Mississippi what’s her name, Fannie Lou Hamer.

Stephen Henderson: Oh, really?

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: And Aavin Cone was standing next to him. He told vice president or President Johnson, that he would not not seat those delegations who were delegates to Fannie Lou Hamer. And you know, I love Aavin Cone by the way, you know, he contributed a lot of stuff to my dad’s archives and brought a lot of stuff together for me. He’s part of that Black Jewish coalition that began, you know, back in the 40s and 50s that really desegregated the city.

Stephen Henderson: So, I think for anybody who is looking for an obvious sign of the power of your dad’s legacy, of course your daughter is now, you know, a great symbol of that. She’s the president of the Detroit City Council. But I also wonder if you look around the city and see other things that for you are a reminder of all of the things that he did.

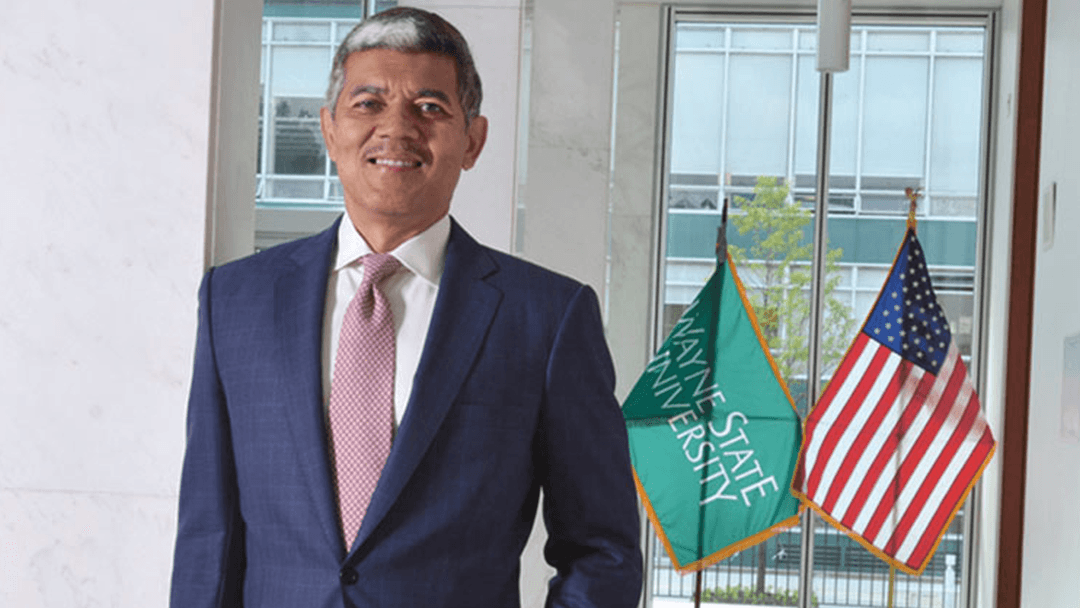

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: Well, I will be perfectly honest with you. When I set out to do this collection, the only support I got was for my sister Laban, who passed. Who wrote a $50,000 dollar check. The rest of it, I had to raise. The UAW put in some money. Some of their archives have been lost and I’m working on an agreement with them. But Dr. Curtis Ivory, at Wayne County Community College, embraced this project, helped me raise the money and actually spent money to have an architectural layout and the build out for where this is going to go.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: So now, Wayne State, you know, I’ve yielded to Wayne State. I want it to be broader because my dad was broader and I knew the issues he had with Walter Reuther. And when I talked to them, they knew there were issues. So we’ve addressed those. But I’m excited and I think, you know, when I look around town, that community college with that many young African-Americans who will get an opportunity to go to college and go on.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: My wife, my wife, who grew up on the eastside, went to Kettering, fatherless, you know. Almost homeless as a teenager, went to that college and she now is practicing medicine in the city of Detroit. So I think that’s a powerful thing because one of the things you know and I know was what they always believed was that education was the great game changer.

Stephen Henderson: Everything, it was everything to them. Yeah, so for just average people who might want to access this, learn about your dad, see this legacy. They can just go to Wayne State..

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: It’s not up on the platform yet. It will be. What’s going to happen is Wayne will house it. It’ll be shared with Wayne County Community College District, where actual physical artifacts from the archives will be on display. We’re hiring a guy, name Joseph Wilson out of New Jersey, who was one of the foremost labor Black labor historians in the world who, when I call him, he told me stuff about my dad, you know, and we’re going to be excited because we’ll be doing seminars.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: Here’s the real power of this. The real power of this is these rank and file people. Micky Welch and people like that I grew up with, you know, the Thomas’s, the Dillard’s, will now have an opportunity for their lives to be opened up to others so that people understand it doesn’t take a whole lot of folks, doesn’t take grand folks, it takes just committed folks.

Rev. Horace Sheffield III: And these blue collar rank and file people changed the history of this city and this nation.

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram @amblackjournal.

View Past Episodes >

Watch American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @amblackjournal.

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*